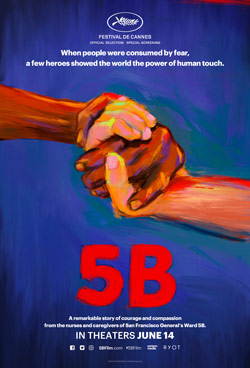

A film revisits the caregivers of Ward 5B, who faced fear and scorn to assist the first AIDS victims

By definition, a hero is someone who displays courage or ability and is ad- mired for their brave deeds and noble qualities. To the men who were encamped at San Francisco General Hospital’s unprecedented Ward 5B, that word was made manifest by the esteemed corps of nurses who displayed care and compassion toward them when so many others refused to do so.

The bonds between these caregivers and their patients is on full display in a heart-wrenching and inspirational new documentary called 5B, which chronicles how the hospital and its caregivers launched the world’s first ward to accept people with AIDS. The film chronicles the efforts of doctors, nurses, and other volunteers whose lived were forever altered while trying to help patients desperately in need.

Read Next | This Is What It’s Like When Heroic Organizations Join Forces

Nurse Alison Moed Paolercia

“It was totally groundbreaking. There wasn’t another unit like this in the world,” says Alison Moed Paolercio, one of the dozen nurses who first opened the unit in 1983. “I don’t think there was another job that I had ever applied for so hopefully as a position in this unit.”

Directed by Dan Krauss and Paul Haggis, 5B is distributed by the Verizon Media outlet Ryot. It’s already been screened at Cannes and premiered in Los Angeles to standing ovations. It’s also scheduled to be released on various on-demand platforms in the next few weeks. Delivered through first-person accounts, the film recounts the many setbacks and few successes of those who came together to deal with the epidemic and try to offer assistance to its victims when no one else would.

Ward 5B was not just a place; it was a remarkable nexus of hope and courage in the face of fear and stigma. Though not a single one of 5B’s first residents survived, the nurses – led by Cliff Morrison – gave their AIDS patients genuine care from the heart and the grace and opportunity to see their last days through with dignity.

Read Next | The Pros and Cons of Disclosure

As physicians encountered what was being described as “gay cancer,” patients were routinely quarantined — isolated amid fears they were contagious.

Ward 5B opened with only a dozen beds. But demand soon outpaced supply, and the unit quickly mushroomed. Just the same, patients were placed in single rooms to provide for their individualized care. Nurses welcomed visits by non-blood relatives and found cots for loved ones to stay with their companions.

“We encouraged the presence of those they saw as family,” Moed Paolercio says. “That could be a friend, a lover, a member of their nuclear family.” Not only did these practitioners care about patients’ pharmaceutical regimens. They also “wanted to know how they were feeling, what other issues were affecting them. We were very conscious of the fact that many of our patients were dying, how that was being experienced, who was helping them, and what they needed.”

Read Next | You Need to Know the Truth about These 7 PrEP Myths

Journalist Hank Plante

Moed Paolercio adds, “Our goal was not only to provide good nursing care, but to provide a healing environment and ensure they felt accepted in our unit.”

Openly gay reporter Henry “Hank” Plante, who provided comprehensive coverage of AIDS for San Francisco-based KPIX TV, describes the impact of these caregivers as life-changing. “They were unafraid,” says Plante, now on-air reporter with the NBC Palm Springs affiliate KMIR-TV. “This was an era when nobody knew how HIV was spread… The nurses and doctors didn’t know if they were bringing this home to their families, and yet that didn’t stop them from doing their jobs. They were really the heroes. They sent a message to those of us in the media that it was okay to touch and love and care for people with HIV.”

While the term “AIDS movie” may elicit expectations about more depressing cinema, Plante describes 5B as “a love story, because it’s about the jobs they did with great love, and that love and compassion prevail in the face of horrible tragedy.”

And Moed Paolercio, who left the hospital in the early ‘90s to pursue her Masters degree, brushes off any notions of her own heroism. “I didn’t see myself as a hero,” she demurs. “I truly saw the patients as heroes. They were the heroes because they as a community helped us to learn how to care for them, and helped the medical community hear what was needed.”

Want Metrosource LGBTQ content notifications? Sign up for MetroEspresso.

Read Next | Finding a Great LGBT Friendly Physician in New York

Last modified: September 13, 2019