I dove into the audiobook version of Jenifer Lewis’ Mother of Black Hollywood without realizing what a fierce ally of the LGBTQ community she has been all along, but I’m pretty sure I would have gone wild for it anyway.

The first thing that struck me about Lewis’ presentation of memoir is her one-of-a-kind voice. If you’ve ever seen an episode of her hit ABC sit-com Black-ish, you know that stage and screen star Jenifer Lewis has a voice that’s rich as warm caramel, expressive as an art gallery, and resounding as an echo in a mountain pass. She uses every inch of it in reading her extraordinary memoir, which turns out to be way more gay than I ever would have guessed – but I’ll get back to that.

After a brief flashback to her childhood, Lewis starts us off fairly close to the present day: she’s already a diva at the height of her powers, heading off on a European vacation (which she describes in delicious detail), and she is about to return to the states to be offered the role of Ruby, the indomitable matriarch of Black-ish.

Next, we travel with our heroine back to her early days as a diva-in-development, joining her as she delivers her first church solo – complete with big belting, back-bends, and a congregation going wild. This segues nicely to her progress into performing — moving to and winning her first roles in New York City; mounting the first of many outrageous, career-defining cabaret shows; earning industry cred on tours.

Mixed with these professional successes, we begin to see that Lewis’ rise to stardom was not all wine and roses. What first appears to simply be a healthy sexual appetite starts to show signs of a addictive behavior: sex becomes a drug she uses to keep from crashing after the potent high of being on stage. She also shows us that notoriety has its downsides, dramatically recounting an incident when some press coverage drew a would-be rapist right to her apartment.

Burgeoning fame also sends Lewis into the path of celebrities — both good (Shirley Maclaine encouraging Lewis to explore her place in the cosmos) and less so (the indignity of Jane Pauley insulting her earrings during an interview). It is also around this time that Lewis begins singing backup as one of Bette Midler’s “Harlettes,” unleashing a series of stories that allows Lewis to demonstrate what is – bar none – the best impression of the Divine Miss M I have ever heard.

Lewis also takes us back to far less glamorous parts of her life: a childhood marked by a multitude of siblings, a stern mother, and slim financial resources. And she bravely shares the ups and downs of a lifelong struggle with manic depression. But for every serious moment of reflection or wrenching encounter with a therapist, there’s a moment of intriguing celebrity dish: Lewis recounts Whitney Houston’s occasionally erratic behavior on the set of The Preacher’s Wife (offering a spot-on impression of the late singer), recalls Whoopi Goldberg offering help to get rid of an unwanted lover, and Barbra Streisand calling Lewis “so special” after a performance. There is no doubt that Lewis has had (and continues to have) an extraordinary life and career.

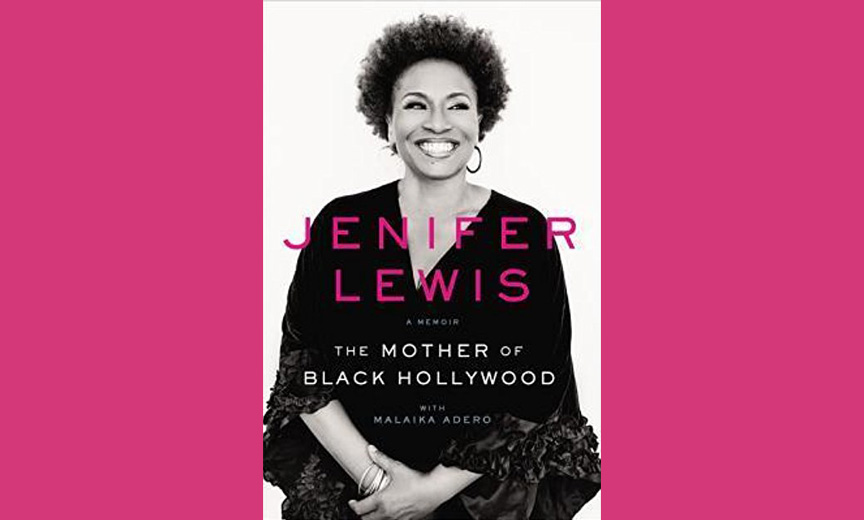

Courtesy HarperCollins Publishers

The Gay Angle of “The Mother of Black Hollywood”

But if Jenifer Lewis is the star of “The Mother of Black Hollywood,” her cast of supporting players is well-stocked with gay men. Foremost among them is the great Marc Shaiman, who wrote original songs for Lewis to slay, has given her a place to stay, hosted parties where she misbehaved, and would ultimately provide her a role on the Great White Way as Motormouth Maybelle.

Lewis also offers a very funny story about finagling her way onto the floor of the Democratic National Convention, which begins with her hair being too big to wear a hat. How’d it get that way? She explains that her friend Brian had “teased up my hair as only a gay boy who had been in the entertainment industry could.”

In one memorable turn of phrase, Lewis recalls a time when she was a habitue of popular gay nightclubs including The Duplex and Don’t Tell Mama (both still in operation today). She describes Irv, a fellow veteran of the nightclub scene, thusly: “As was the fashion among gay men of a certain age and showbiz types of the time, Irv called everybody, ‘Mary.’ I loved that!’”

Perhaps most significantly, as an individual who worked on the stage and screen throughout the height of the AIDS crisis, Jenifer Lewis went through it. Heartbreakingly, she reports losing two to three friends a week over a period of years. In addition to exploring the grinding misery of such constant loss, Lewis also focuses in on certain deaths that affected her profoundly. She notes that when her friend Will died of “advanced pneumonia,” she was told: “You cover up before you go in there ‘cause you don’t know what this is.” And you can feel Lewis’ heart ache for the loss of the “grandeur, splendor, and beauty” of her friend, fellow performing artist Quitman Fludd. Had Quitman not been gay, “he was the only man I would’ve really married,” Lewis reveals. And toward the end of his life, when she goes to visit him as he suffers from end-stage AIDS, Fludd tells her she is the first person to touch him without gloves in two years. Lewis ultimately ends up singing at many funerals and fundraisers, and her description of a traumatized audience responding to her rendition of Stevie Wonders’ “They Won’t Go When I Go” is truly moving.

On a lighter note, Lewis’ list of show business inspirations reads like that of many a drag queen, including divas from Aretha Franklin to Judy Garland to Mae West to Bette Midler. Regarding Midler, here’s how Lewis describes revealing to the crowd at a sold-out show that she had been cast as a Harlette: “When I announced that I was leaving to become one of Bette’s Harlettes, every fabulous queen in the club lost their damn minds!”

And while the book is lighter on lesbian representation, Lewis does make a point of pondering how her own butch nature affects the role she has often played in romantic relationships. “Everybody in the world knows I’m the man,” she says. “How I am not a lesbian, ladies and gentlemen, is beyond me. But when you’re a dick diva, you’re a dick diva!”

Jenifer Lewis is a diva in the best sense of the word. Even if you’ve not been previously familiar with her, you will leave this masterful performance enraptured. And if you already know and love her work, you’re bound to walk away loving this Mother all the more.

This review is based on the audiobook version of The Mother of Black Hollywood: A Memoir ($24.99, HarperAudio) as read by the author. It is also available in hardcover ($25.99) or paperback ($15.99, HarperCollins Publishers). Read a review of another great audiobook or see all of our books coverage to find more of our top picks for LGBTQ readers.

Read Next | Finding an Outstanding LGBT-Friendly Lawyer in New York

Last modified: October 21, 2019