Richard Renaldi captures the decadence of a club scene now that it’s no longer shaken by fear of an untreatable disease.

In 1996, after a breakup with his boyfriend, Richard Renaldi learned he was HIV positive and abruptly retreated from years of late night partying in New York City’s swirling club scene. He discovered he was “extraordinarily lucky” to have seroconverted just as a new class of lifesaving drugs entered the market. He quit his job as a photo researcher and focused more seriously on his own photography.

As he resumed dating, Renadli entered into a relationship (now nearing two decades) with architectural photographer Seth Boyd, who was much less experienced in club culture. Encouraged by Boyd, Renaldi returned to the club scene seven years ago, snapping images of revelers in the hours after last call and lights up as they made their way home Sunday mornings.

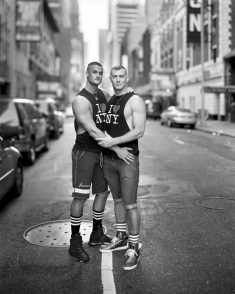

Renaldi documents that transformed club culture in his fourth book, Manhattan Sunday, published by Aperture. Many of his 130 images were on display at the Eastman Museum in Rochester and then the Aperture Bookstore Gallery in New York earlier this year. They will also be exhibited at Transformer Station in Cleveland, Ohio in April 2018, followed by the Robert Morat Gallery in Berlin, Germany the month after.

“Nightclubs are templates onto which we can project our fantasies, basking in the surreal spectacle of a sea of men getting down and getting off, the intoxicating sound of tribal house music mingling with the scent of pheromones,” Renaldi, 49, writes in Manhattan Sunday. “Anonymity, familiarity, and desire intersect on the synthetically charged dance floor, and in the age of advanced HIV prevention and therapy, the club scene is today somewhat less encumbered by a sense of mortal dread.”

Renaldi finds intrigue in the experience of stepping from the swarm of a thrumming nightclub environment out into the relative calm of the streets as the reveling denizens head home. “The inspiration for the book was that contrast, and a depiction of the city at its quietest,” says Renaldi. “New York is usually 24/7 so the quietest time is on Sunday mornings. There’s something sort of magical about being in such a megalopolis, and the backdrop of people leaving the clubs.” This photographic journey of Manhattan Sunday includes moments both intimate and passionate: couples holding hands, portraits of surreally serene clubgoers, tranquil streetscapes,and even workers sweeping up post-party detritus.

Born in Chicago, Renaldi took up photography while in high school. He first entered the club scene in Chicago (though as a minor, when he could only attend juice bars), before diving in head first in New York City — where he graduated from NYU with a BFA in photography — and has lived for more than three decades. He says that he was initially seduced not only by the sensory thrill of men, music and lights, but by the opportunity the clubs afforded to transform into a “fabulous, extravagant self.”

Over time, the atmosphere has noticeably changed from when he first was coming out, frequenting places like the Sound Factory, when the scene became desexualized amid the onset of AIDS. Now he says, “I think slowly but surely it’s returning to the looser pre-AIDS era where anything goes.”

“The constant is people’s desire to have that kind of release, the letting-go experience, and the human desire and glamour and attraction to these things that have been with us for a very long time and will continue to be,” says Renaldi, who was named a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow in Photography in 2015. He is now pursuing an archival project with a broader range to explore nightclubs from the 1980s up to the present day.

Of Manhattan Sunday, Renaldi says he hopes audiences will “take away a sense of beauty, a sense of something that’s maybe hidden to them that has been revealed. I hope they take away a sense of the gorgeousness of these very diverse people of both genders, sexual preferences, gender identifications, and races and in the context of this incongruous, grand, beautiful city that leaves an impressive mark on them.”

Eric Schwabel — The Psychology of Shooting

Diane Arbus: In the Beginning Gallery

Last modified: July 26, 2018