LGBT people take their lives four times more often than the general population. LGBTQ people of color are at exponentially higher risk.

In order to address the specific challenges they face, journalist Antoine Craigwell founded DBGM, an organization that helps people of color deal with a multitude of the challenges that arise from issues that range from racism to transphobia to mental health and the stigma still attached to HIV.

Now New York will be home to the fifth conference addressing those concerns and more next month. This year’s DBGM conference is titled “In My Mind — Overcoming Barriers; Creating Opportunities.” The two-day event is planned for Oct. 10 and 11 at The New School in Manhattan.

Beginnings

“I started the organization in 2010,” says Craigwell, who remains CEO. “But DBGM became much more formalized in 2013 after the success of a documentary I made called You Are Not Alone in 2012. The board recognized fairly early that they wanted to focus beyond mental health in the black gay community and reach out to include mental health concerns for people of color worldwide.”

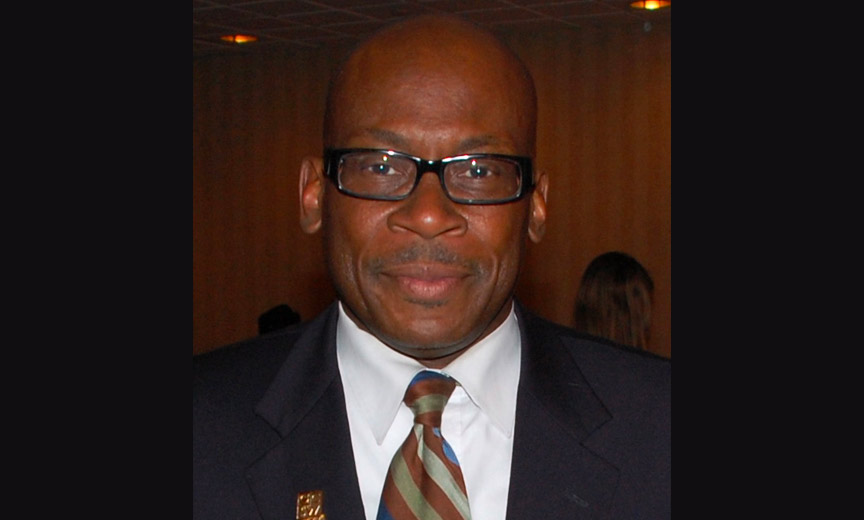

DGBM CEO and founder Antoine Craigwell

The reason for his activism, he says, is simple: “Because nowhere is anyone paying attention to the mental health in people of color.”

The first year, he recalls, “we decided to have a summit on Rutgers campus. And immediately, there were some significant markers that told us how great the need was. One was that even though we announced that registration was at 8 AM, there was still a line of people trying to get registered at 11 — even though we were due to end at 4 in the afternoon. And once 4 o’clock came, there were still people waiting to see what else we might have to say and what else we could talk about.”

More From MetrosourceThat summit led in turn to a full day DBGM conference at Mt. Sinai in 2015. Secure in the knowledge that there was an audience and a community overflowing with people in need, Craigwell proceeded, and began to pick up allies along the way.

Allies and New Traditions

“That’s when we began to establish some traditions,” says the founder. “For example, we’ve invited the Native American two-spirit community to open the conference with an invocation, and that became well accepted. We’ve also instituted a moment of silence for those who have either lost their lives or had their lives taken over the past year, and this year that will be delivered by a Latina trans woman. We call it ‘remembering our own.’

“With each year, we’ve been evolving, too,” Craigwell explains. “In fact, after inviting people to evaluate the conference, one of the things we heard was that there were too many issues to deal with in a single-day conference. And we thought, ‘we were barely able to pull all this one-day event together!’ But that’s what people told us they needed, and so we just told ourselves, ‘We’re gonna do this for two days.’ And we decided to run with it.”

One of the DBGM conference mainstays is Massachusetts’ Dr. Gary Bailey. As one of the first presenters at the event, Bailey helped shape the curriculum in its formative years. “I came to participate in its first iteration,” he says, “given my background as a clinical social worker and as a black gay man, sex orientation, race, class, and social location are all part of my intersectional being. So the conference helps align with my core values and beliefs as they relate to the stigma of utilizing mental health services.”

Dr. Gary Bailey

The DBGM conferences are unique, Bailey adds. “This conference brings together both the practice community, members of the academic community and those who are the direct providers — especially those people on the ground doing work on HIV and with the trans community. It brings together thought leaders to talk about best practices and emerging issues.”

Why It’s Vital Right Now

To that point: “Since the travesty of the last presidential election, we have to pay particular attention to what’s happening in Washington and the carve-backs in our community, because we’re losing LGBTQ quality of life in general as well as in areas related to people of color specifically.

“I participated because the conference allows for people to come together like minded interested in issues and areas of practice, provides a space where ideas get exchanged and there’s a diverse menu that includes healing circles on the one hand and restorative justice sessions. How do we address people who have been incarcerated and make them whole again. Statistics tell us that black and brown males are disproportionately represented in the justice system. And we know that practices like ‘stop and frisk,’ and arrest are inherently racist. And with something like cash bond in the criminal justice system, you have people who can’t make bail sometimes in jail for two years before facing trial. So it’s a gateway to the system.”

A Multi-Layered Approach

Craigwell and Bailey agree that the problems are as systemic and institutional as they are spread across the spectrum from external and practical solutions to the internal healing caused by decades of abuse — either at the hands of society in general, or sometimes within the very families where they were born.

“For the people attending over the last five years, the news that the system is flawed is not new,” Bailey asserts. “But you cannot discount how important it is to have our own reality validated. Being in those spaces and hearing you’re not alone in being vulnerable, in my reaction to police violence, in my feelings about HIV stigma or trans issues or mental health? You cannot underestimate that.”

What the World Needs Now

Could either of them imagine a world where a DBGM conference could ever become obsolete?

“Well,” Bailey concludes, “We cannot get to the place of full equality until we have the difficult conversations about how we got to this position. That’s about undoing racism undergirds white supremacy and class war against the working poor in the country. And if we can’t name it, we can’t change it. Racism is one of the key risk factors for identifying poor outcomes like infant and maternal mortality, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

“Conferences like this will become unnecessary when we have an equity lens, not just an equality lens,” Bailey says. “It’s not about having a seat at the table. Tt’s creating the table, and that’s the difference.”

Want Metrosource LGBTQ content notifications? Sign up for MetroEspresso.

Last modified: September 23, 2019