Historians regard symbols as one way of determining the unique characteristics of a culture. Sometimes the signifiers are auditory — much the way first responders’ sirens vary across the globe. But some of the most powerful tell their story visually in an instant. The study of those cultural transmissions is known as semiotics, and those images include not only the pyramids , but Stonehenge and the Stonewall Inn.

Now a USC professor has assembled a book that zeroes in on they many ways we’ve sent our often-coded messages ricochetting through LGBTQ culture. That includes a time before it was legal to even appear queer in a public space identifying as anything other than cis heteros.

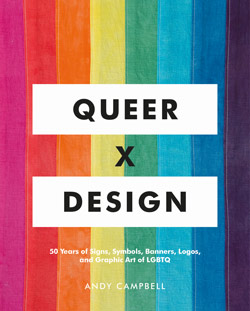

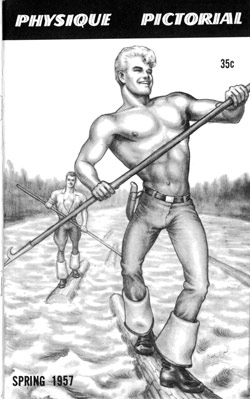

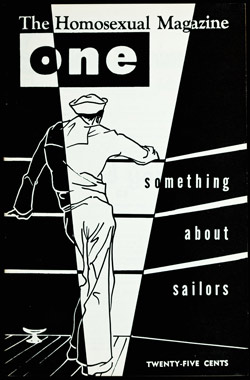

Andy Campbell is an Assistant Professor of Critical Studies at USC’s Roski School of Art and Design who teaches critical studies history and theory to artists and designers. What he’s assembled in Queer By Design: 50 Years of Signs, Symbols, Banners, Logos and Graphic Art of LGBTQ is an anthology of our trek from invisibility into Pride and beyond. It’s a fascinating record that contains images that also predate the Stonewall rebellion by a more than a quarter century.

Campbell says it was the dearth of those signifiers collected in one place that told him his collection would fill a void. “The impetus for the book was that I was looking at such a range of LGBTQ scholarship,” he says, “and there really is so much in so many different areas. That’s when I started to identify places where people hadn’t already put a lot of energy. And I found that the same was not true of LGBTQ design. So I started by creating a list of 150 images or so, and thought about what objects would tell the most interesting and dynamic story about LGBTQ communities and histories, and I went from there.”

Between the covers of Queer X Design, you’ll find photos that delight, artwork that seethes with rage, and images that have united the LGBTQ community in victories and setbacks throughout the struggle for equality.

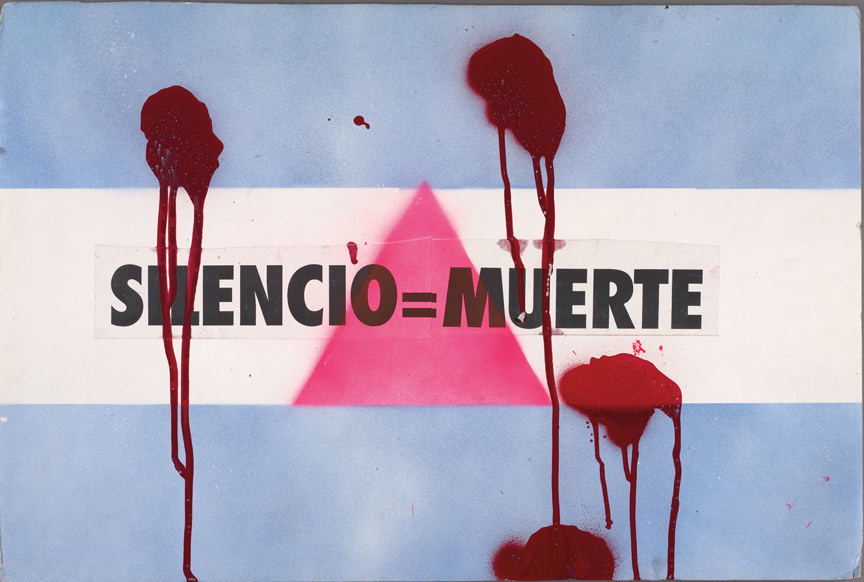

If one overarching theme jumps out, it’s the need to address police surveillance and violence. “Early on, we were simply outlawed,” the author says, “and a lot of early LGBTQ imagery and material was dedicated to not only making an argument about the validity of our existence and networking within our own communities, but countering overt state interference. One of the throughlines in the book is that tension, going all the way up through the Black Lives Matter movement. Black Lives Matter is included in the book as an example, not only because two of the three founders of that movement self-identify as queer — but also because structurally, they’re essentially fighting for the same thing. They’re activating against police surveillance and physical violence. Like Black Lives Matter, for LGBTQ people historically, police violence was the awful occasion for organizing around a host of other issues as well.”

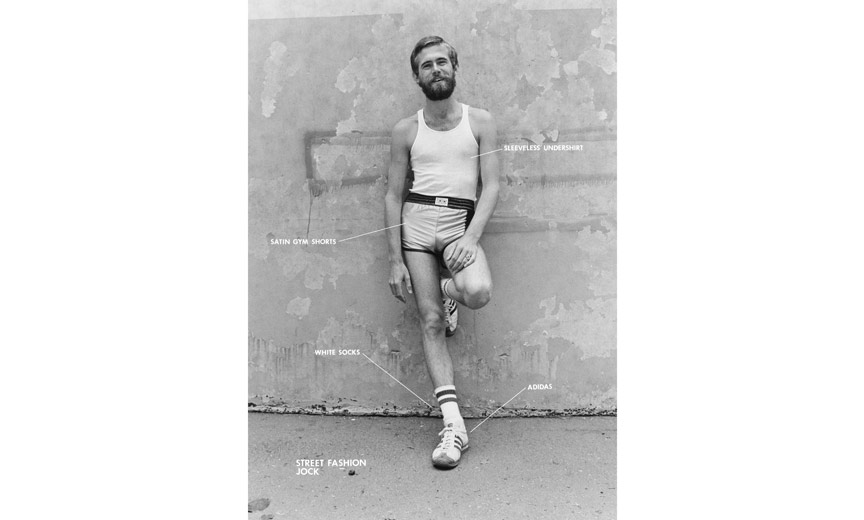

But Queer X Design is much more than pages of rage. “I also love Hal Fisher’s gay semiotics photographs,” Campbell says with a chuckle. “They were meant to be tongue-in-cheek, and Fischer, who was a photographer and an art critic, brought a healthy dose of Jewish humor to that project. He was living in San Francisco and making note of all the different ways men identified through what they wore. So he sort of pokes fun by creating these typological photos, feigning an anthropologist’s tone. But these photos, which are accompanied by an essay on gay male signaling culture, also have the capacity to teach the uninitiated how to identify with different elements of the community. It reveals something of an in-community way of identifying to a broader audience. There’s a kind of camp sensibility you can appreciate about them.”

[wpp range=”all” cat=’16259′ thumbnail_width=75 thumbnail_height=50 limit=4 stats_views=0]

Included are both the AIDS quilt and the evolution of Gilbert Baker’s rainbow flag. “That’s really fascinating,” says Campbell. “In putting this book together, I found out a lot more about its history, and how it has never really been this static symbol. Initially, there were two large flags made, each with eight colors rather than the six that we know today. One of the flags had tie-dyed stars in a blue canton — similar to the U.S. flag. This original version of the rainbow flag is all but unknown today, and I think would surprise most readers. The story I tell is about the Pride flag’s change. Now cities like Philadelphia and designers like Daniel Quasar are adding brown and transgender stripes to it as well. People get grumpy about it changing, but it’s been in flux from the very beginning.”

In assembling Queer X Design, Campbell noticed another disturbing trend: as LGBTQ Americans have become more visible and accepted, their output of cultural expressions have both dropped off dramatically and been increasingly appropriated by corporations looking to cash in.

From his vantage point, Campbell asserts that our narrative has been one “of ever-evolving innovation around our visual symbols. And the activist is always trying to imagine the future. The LGBTQ community has always been future-oriented in that way.”

Read Next | This Week’s Best LGBT Events in New York City

But while collecting images, Campbell says, “I did arrive at a place of a little trepidation, and that’s how difficult it was to find visual examples of our movement in the 21st Century, which sounds surprising. So many of our signs and symbols — maybe it’s too strong a word — but “co-opted” is what comes to mind. You know, it’s not enough to see a corporate logo done in rainbow colors. That’s not what we have historically fought for. But that’s something I deal with in the book, that tension between assimilation and valuing difference as difference. As we have become assimilated, it has come with so many great things. But I think it’s important to have an identity that belongs to us in how we engage with queer symbology. And I have full faith in LGBTQ artists and designers to imagine a better future.”

Want Metrosource LGBTQ content notifications? Sign up for MetroEspresso.

Last modified: July 17, 2019