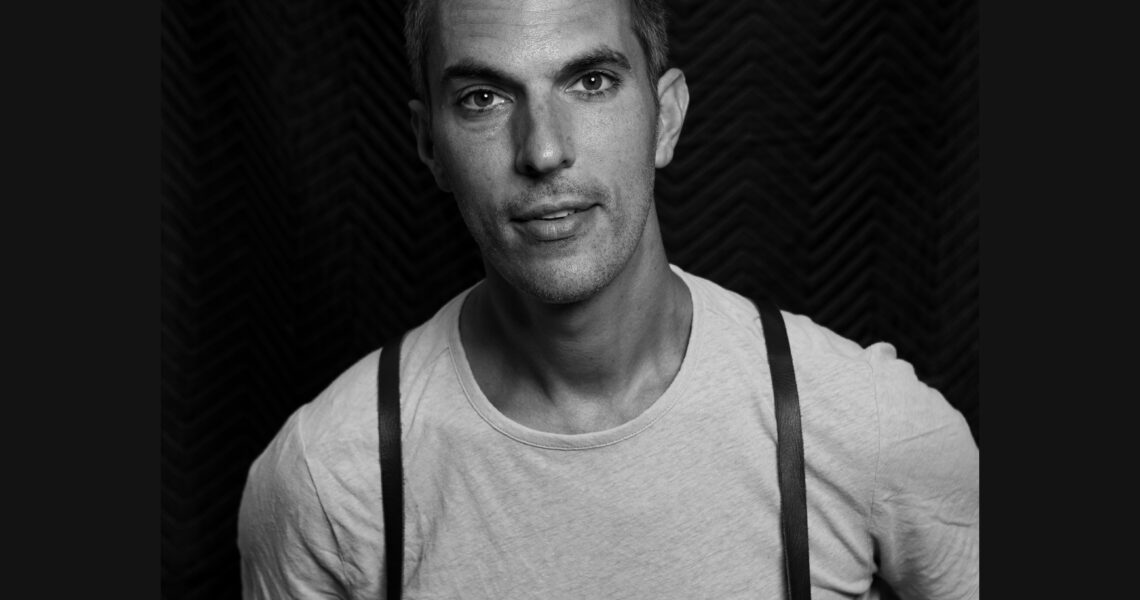

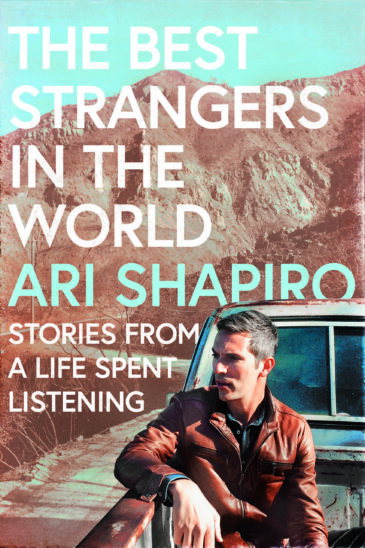

Having grown up listening to National Public Radio as a kid, it might seem pre-ordained that Ari Shapiro would someday become the ubiquitous voice of NPR’s flagship news program All Things Considered. But things are rarely as simple as they might appear on the surface. Ari Shapiro was somewhat of a unicorn growing up Jewish in Fargo, North Dakota in the 1980s. By the time his family relocated to Portland, Shapiro would come to terms with another layer of his identity as a gay teenager. Shapiro has since racked up an impressive resume that includes a twenty-year career at NPR as well as an enviable side-hustle performing with the world renowned, genre-spanning band Pink Martini. Shapiro’s circuitous path to becoming the ultimate multi-hyphenate phenomenon that he is today is unpacked and dissected in his new book The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent Listening. The book, which has earned rave reviews and became an instant New York Times bestseller upon publication, is an engrossing and enlightening read, chock full of amusing anecdotes and life lessons, big and small which touch the heart and soul.

There is something very unusual about the relationship that I as a journalist have with people who I meet in the course of my work, because I might only interact with somebody for 15 minutes or an hour ever in their entire lives and we might never see each other again. And yet, those 15 minutes, or that hour together, can create a profound connection that is no less real, for being fleeting. And so, when I talk with somebody who may be experiencing the worst day of their lives, whether it’s a natural disaster, or a war, or a mass shooting, the act of them telling their story, and me, really listening, and allowing them to share their experience with me, is a form of communion that I do not take lightly. The phrase, The Best Strangers in the World, comes from a work of art that a friend of mine created, having nothing to do with my occupation. But I think it’s a very apt phrase, to describe the sort of beautiful and unusual privilege that I have to connect with people all over the world in such a wide variety of circumstances.

In the introductory chapter, you share the story of how you came out to your parents while you were still in high school, before you’d even kissed a boy. Tell me about how you had the courage and the presence of mind to do that so fearlessly at such a young age.

I remember thinking to myself, I’m going to have to do this sooner or later. And the sooner I do it, the sooner I can get on with my life, the sooner it will become a non-issue. And it’s never going to be easy. It’s never going to be painless. So I might as well just take the plunge. And as I say in the book, this was before I had even kissed a boy. It’s not that I was living a double life. It was that I didn’t want to live a double life. I wanted to figure out what this piece of me meant integrated into all of the other pieces of me. And I thought the only way to do that was by being honest and starting that process of discovery in a transparent way.

The year was 1988 – which means Shapiro was likely around 10 years old. Monette was discussing his latest book “Borrowed Time: an AIDS memoir” which was considered a groundbreaking and profoundly personal firsthand account of the AIDS epidemic.

I remember hearing the interview and the respect that Terry Gross gave him as a gay man. And thinking that it was the first time I had heard a gay person listened to and spoken to as somebody worthy of their time and attention. Until then, the only stories I had seen and heard about gay people were either stereotypes and caricatures, or as villains or people dying of AIDS. So, I remember that moment, thinking oh, being gay can mean something more than just the stereotypes that I had seen in pop culture.

One of your early assignments at NPR was responding to listener mail. And then, when you became a bona fide journalist in your own right, you got your own mail. And you share some of those letters, some of which were not complimentary. One called you a “faggy, pushy, annoying smart-ass” and another told you to “Butch up.”

I love hate mail. I think when somebody takes the time to write in and say something, even if it’s something hostile and rude, it means they were listening. It means they were paying attention. And if they didn’t like what they heard, I’m happy to get a letter in the mail that informs me of their views on the program I’m making. And so I love hate mail. I collect it and, as I describe in the book, display it for people who stop by my office to see.

One of my favorite chapters “You Can’t See Schvitz on the Radio” deals with your propensity to sweat profusely. It’s something you address very candidly in the book with a measure of humor. Amidst your impressive achievements, it’s reassuring to see that you have human foibles like the rest of us.

I wanted that to be kind of a break from some of the heavier things in the book. I think it’s important for people who are successful to talk about the moments that they have struggled and failed, and experienced setbacks, because it’s easy for people to look at successful individuals and assume that success is the opposite of failure, when in fact, failure is a step on the path to success. And every successful person I know has failed in myriad ways. And if we don’t talk about that, then people experiencing failure will feel like they’re doing something wrong, when in fact, you’re doing something, right. Because if you’re not failing, you’re not challenging yourself.

Shapiro describes another incident in the book in which a seeming failure turned into a fortuitous experience that would go on to pay unexpected dividends. Shapiro was approached about developing a one-man cabaret at an event space in Georgetown. Not one to shy away from a challenge, Shapiro attacked it with characteristic gusto, crafting an ambitious piece that drew on his experience as a foreign correspondent, learning lyrics to songs in six different languages. Much to his surprise, the first performance went so well that he decided to try to replicate it at Joe’s Pub, one of New York’s most venerated performance venues. Booking a gig at Joe’s Pub gives one immediate street cred, so the stakes were substantively higher. When his performance fell short, it shook his confidence. As he writes in his book: “I beat myself up, trying to fight the growing suspicion that I was just a pretentious dilettante and a poseur.” But he still had one more show to do and Alan Cumming – yes, that Alan Cumming — was coming with his husband to see his show. Ari and Alan had crossed paths before at various functions and had struck up a camaraderie. Ari dreaded the thought of bombing in front of his celebrity pal, but then inspiration struck. He asked Alan if he would join him on stage for a Scottish number that was part of his act. Luckily Alan was game and this time, the show was salvaged.

The thing that I said earlier about failure applies to this as well, because when I did my solo show at Joe’s Pub, I thought that it went terribly. But Alan Cumming sang a song with me as part of that show. And years later, he and I created a show together, which we are still performing all over the country. We just finished a sold-out two-week run at the Café Carlyle in New York. That would never have happened if it weren’t for the moment at Joe’s Pub that I thought went terribly. It underscores the point about failure being a step on the path to success rather than the opposite of success.

You’ve played some prestigious venues as a member of Pink Martini including Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl. Café Carlyle has its own aura of prestige. What was it like performing there?

It felt like such a privilege to be in that room on that stage, where so many legends have performed over the years from Elaine Stritch to Eartha Kitt. There’s a moment in the show where Alan sings a song and I step back. And my temptation was to lean against the wall. And then I realized that the wall is painted with a beautiful mural that has been there for decades and is an important work of art. And so to be able to bring our show to that space was an experience I will never forget.

Shapiro credits his friendship with Cumming for providing the impetus to write the book.

One of the things that Alan taught me is to keep challenging yourself and keep doing things that are scary and risky and that you might fail at. For me, writing a book was one of those things. I have a lot of experience telling stories on the radio. But those are stories about other people. Writing a memoir is very different because first of all, you’re writing for the eye, not for the ear. Second of all, I’m at the center of the story, as opposed to the people I’m talking about on All Things Considered. So that was scary, and it was a risk.

In the chapter titled “The Whole World Falls In” you talk about your annual pilgrimage to a commune in a remote area off the grid in Nashville where you spend a week with a diverse cross-section of LGBTQ+ folk who identify as “radical faeries.” The movement has been described as a countercultural movement seeking to redefine queer consciousness. As a card-carrying faerie, having attended these gatherings since 2008, you say in your book how the experience has affected the way you move through the world, including the way you practice journalism.

You know, the thing that I love about the Faeries is the way that it allows intergenerational connection, which I think is so hard to find in queer spaces. Most places that LGBTQ people gather these days, is very segmented along generational lines. And I think the Radical Faerie movement is one of the few places that allows LGBTQ people to learn from their elders, and particularly in moments of adversity like this one. The fact that queer people who may never have fought these battles before, can talk to people who lived through the AIDS crisis, or lived through the Stonewall riots, or dealt with other forms of hostility that have so defined LGBTQ life is really important. I think one of the things that has defined queer existence in the United States and around the world, is finding a way to not only survive in the face of hardship and adversity, but to thrive and experience joy in the face of that hostility. And so the Faerie movement, I think, is key in that it allows us to learn from those who came before us and not have to reinvent the wheel every time it feels like we are facing a significant hurdle that may seem insurmountable.

In light of what’s going on in the United States with DeSantis and the “Don’t Say Gay” law and the book banning, what is the best strategy to mount a resistance?

My role is not to strategize how to mount a resistance. Somebody once asked me, how I can use my experience and identity. My answer was, I don’t see my role as trying to influence, I see my role as trying to illuminate. My goal is to help people better understand each other and the world that we live in. And so, I think about empathy, I think about how to view the world through the eyes of others. And I think about how to better bridge the divides that are separating us. And that’s not to dismiss the importance of those who strategize and campaign and influence, but that’s not me.

In the book, you describe how you and your brother were kind of junior ambassadors for Judaism where you grew up in North Dakota because there were so few Jewish people. In terms of your Judaism, how would you characterize your Jewish identity and how does it overlap with your gay identity?

I think being a member of any marginalized group allows you to see the scaffolding of society a bit more clearly, because fish are not necessarily aware of the water that they swim in. And if you aren’t certain whether you belong in that water or not, it’s a bit easier to perceive it. And so, I’m Jewish, but I’m not observant. I celebrate the holidays. My husband and I have a Passover Seder every year, but I think one of the most important things that Judaism taught me was a culture of questioning and not taking things for granted and always asking why. And that’s something that applies to my work as a journalist every day.

Last modified: July 8, 2023