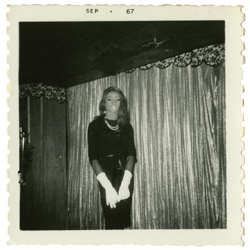

Trans Soul Singer Jackie Shane, who died at her Nashville home in February 2019, insisted on performing and living life on her own terms — until she suddenly vanished.

Back in the swinging ‘60s, there was a transgender R&B singer who headed from the racist and homophobic scene in Nashville up north to Toronto, where she would go on to build a sizable cult following. This performer was breezy and confident — raised on gospel music and blessed with a voice that could croon as soft as velvet to sing Dee Clark’s “Raindrops” then turn equally gritty for “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag.” Over the course of her career, she took to the stage in women’s and men’s clothing, drawing fervent fans across the border from Detroit and over the ocean from London. She made sizzling soul records. One of them — “Any Other Way” — made it to #2 on the local charts, garnering airplay in major cities both in Canada and the U.S.

Though there was interest in her from labels including Motown and Atlantic, she turned both down to record on indie labels. And though she performed on regional TV, she refused to be on American Bandstand because black people weren’t allowed to dance on the show at the time and The Ed Sullivan Show because they asked her to tone down her look. Before Bowie, before Sylvester, before Janelle Monae she was a true original who both performed and lived on her own terms. And when she disappeared from public life in 1971, many people thought she’d died. But she is very much alive, and now she’s back with a box set that’s burning up Spotify.

Never heard of her? You have now: meet Jackie Shane.

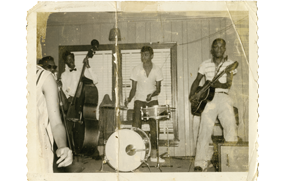

Shane was born in Nashville in 1940 and raised in Nashville and Ohio. Although the area was (and continues to be) known for its Country & Western scene, that was not where Shane was looking to make her mark. Like so many Nashvillians, she worked as a studio musician and backed such major blues artists as Big Maybelle and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and R&B acts including Larry Williams, Little Willie John and Joe Tex. She also co-wrote and played on the hit ”I Miss You So,” recorded by Morgan Babbs, although she was not credited for her work.

Her early accomplishments included winning a talent contest hosted by bandleader Johnny Otis (while she was visiting her mother in LA). Shane went on to blow away singer Jackie Wilson — prompting Wilson to pay her not to perform rather than risk looking less dynamic by comparison — and Soul mainstay Joe Tex, who encouraged Shane to hit the road. And hit it she did, traveling from Detroit to Cornwall, Ontario and onward to Montreal, where she met musician and bandleader Frank Motley.

With Motley, she would go play Montreal, Boston and Washington, D.C. During this period, Shane wrote the songs “Chickadee” and “Slave for You Baby”, on which Motley would later surreptitiously add his name to the songwriting credits. Shane would later point to this kind of dishonesty as one of the reasons she came to mistrust the music industry.

Jackie Felt So Free

Of her initial travels to Canada, Shane said: “I felt so good. I never felt that good before. I felt so free.” She would ultimately go on to think of Canada as her home — even though back then it was not the paragon of LGBT acceptance it would go on to become. Even there, Shane was forced to wear a coat to disguise herself when she went out on break between sets at clubs — to avoid being arrested for wearing women’s clothes.

Shane is careful to clarify that, though she is a performer, she is not doing drag but rather affirming her right to be herself. “I was born a woman in this body. That’s how it’s always been,” she said. “I’m not putting on an act. I could not be anyone else if I tried. It would be the most ridiculous thing in the world for me to try to be a male.”

Still, it often wasn’t easy to be herself. Shane faced several scary encounters with gangsters. One threatened her when she turned down his romantic advances. Another kidnaped her, only to let her go when she told him she was underage. But fear didn’t stop her from working, and on stage she was totally uninhibited. Picture her with a driving, funky backbeat thumping as she says, “You know, when walking down Yonge Street — you won’t believe this — but you know some of them funny people have the nerve to point the finger at me and grin and smile and whisper. But you know that don’t worry Jackie because I know I look good, and every Monday I laugh and grin on the way to bank because I got mine. I look good, I got money and everything else I need.”

Audience response was overwhelmingly positive. “You know what the people would come to me and say?” Shane recalled. “‘Jackie, talk to us more because you say things that other people don’t say.’ This meant a great deal to me because I’m giving them a part of me. Being for real, telling the truth, letting them know that this is real, that I am real, that I feel this, that this is me!”

Etta Would Have Gone on First

Big names took notice. Shane’s passionate cover of “Any Other Way” (recorded in one take) got compliments from the song’s composer William Bell. Shane even opened for Etta James. At the time, her sets were so intense, audiences were known to overturn tables. After one such show, James reportedly said, “If I’d have known this, I would have gone on first!”

Shane began to book TV appearances, including Night Train — a local show broadcast in Nashville — and on the CBC-TV show Music Hop. When she played the Sapphire Lounge — a frequent stop in Toronto — she negotiated to make sure her audience would not be blocked at the door. She told an owner of the club,:“Look, gay people must be able to come and see me. I don’t want anyone kept from seeing me. I want them to come.” Gay, straight, Black, white, they packed the Sapphire Lounge to see Jackie Shane.

As the ‘60s wound down and the dawn rose on the ‘70s, Shane was still in the groove. She played Nashville to an integrated crowd with drummer Buddy Miles; played shows from Albany to Las Vegas; played tambourine on Joe Cocker’s “Black Eyed Blues” and met George Clinton and his flamboyantly irreverent band the Funkadelics in Toronto. Of them, she said, “I liked what they were doing, but it’s not me. They were a bit much for me.”

Jackie worked with Frank Motley less often as he became increasingly violent and unstable. When he showed up drunk for an all-ages show, the promoter promptly cancelled it. After he refused to pay Shane for a gig, she decided she would never work with him again. And then Shane walked away from it all. First, she helped take care of her mother — in California and later Nashville. Then after her mother’s death, Shane stayed in Nashville, living quietly, rarely going out. But Shane’s time in the public eye was only on pause.

Find LGBTQ-Friendly ResourcesJackie’s Fans Want Her Always to Be Remembered

A 2010 CBC documentary by Elaine Banks was the first sign of renewed public interest in Shane. Eventually, The Numero Group, a Chicago-based label, expressed interest in releasing Shane’s music — including her singles and a long out-of-print live album. Years of collaboration eventually led to Any Other Way — remarkably the first album in her storied career that Shane actually approved.

When Douglas McGowan, an A&R person with The Numero Group who would become lead producer for the 2-CD set, came to her house with the contract, Shane, still a recluse, would not let him in. He left the contract on her doorstep. Eventually she signed, and the rest is herstory.

Of Shane’s reaction to the renewed interest in her work, McGowan says, “She was flattered; she was surprised. She felt a variety of emotions [about] how important she was to a lot of people. She knew she was doing something right [but] she doesn’t need anyone else’s validation.”

Looking back at how Shane was able to find an audience in her heyday —so long before the LGBT community achieved wider acceptance, he observes: “She was the right amount of ‘other’. The people were in a position to appreciate her for the incredible talent that she was and not be hung up on … a certain homophobic mindset.”

Why Toronto? “Jackie probably went where the appreciation was,” McGowan guesses, “where the acceptance was and where she felt safe. Toronto was that place.”

“The thing for Jackie has always been to live life on her terms without ever wanting to wade into politics or debate. [Yet] everything Jackie does is political in spite of herself,” explains McGowan. Indeed, sometimes she has been more overtly political — advocating for the March on Washington in 1963, performing in East LA when other artists would not due to the epidemic of drive-by shootings, and when Trump announced a ban on transgender troops, she raised funds for LBGTQ causes by making her music available on Bandcamp.

“There’s this whole world of people who are out now and enjoying a lot more mobility than she ever did,” says McGowan. “I think she’s happy about it. But I think she has also expressed many times that any kind of celebration should be tempered by the fact that it always should have been this way, [and] there’s a lot left to be done.”

Looking back on her legacy, Shane says, “I hope that I gave them something that they will always remember. I gave what I had. I talked to them and I was simply saying, ‘Live and let live.’ We all want a little piece of it. And we should all have a little piece of it. I really left an impression on these people, and I’m glad, but I gave them me, honestly and truly and completely. These were people who were not accustomed to a person like myself, but they learned to like me — being trans and being different. These people had never been exposed to a person that was for real.”

Want Metrosource LGBTQ content notifications? Sign up for MetroEspresso.

Last modified: February 26, 2019