Billy Porter knows how to make an entrance.

Raised in a conservative Christian home, Porter spent much of his early life shunned by family as “an abomination.” He’s been pushing back ever since. As an actor, singer and Broadway star, his every public act and pronouncement could be seen a demonstration of Pride. And when he stepped onto the red carpet at the Oscars dressed to slay in a Christian Siriano tuxedo gown, he put Planet Earth on notice: He’s here, he’s queer and he’s not going anywhere.

And then, just to prove he can ring that bell whenever he pleases, Porter beat his best at the Met Gala earlier this month. Borne aloft on a litter by six shirtless musclemen, Porter reclined bedecked in an Egyptian-inspired “Sun God” ensemble by The Blonds. It was a moment that Vogue magazine called “the most fabulous entrance in Met Gala history.” His ensemble boasted a 24-karat gold headpiece, a bling-festooned catsuit with 10-foot wings and custom gold-leaf Giuseppe Zanotti shoes. And because that wasn’t loud enough, Porter turned up the volume with jewels from Oscar Heyman, Andreoli and John Hardy.

Yes, after nearly a quarter century working as an entertainer, Billy Porter is now at last a celebrity.

Anyone not looking closely might guess it all happened overnight. In 2013, his breakout role as Lola in the Broadway hit Kinky Boots landed him a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical. Only a year later, he took home a Grammy for its cast recording. He’s released four albums over the last decade, and in 2018, his career got an unexpected boost when producer Ryan Murphy cast him as a gay warlock in American Horror Story: Apocalypse then turned his bit role as Pray Tell into one of the defining characters of the ballroom culture series Pose. The only one not surprised by his sudden ascent to the A List? Billy Porter.

Born in Pittsburgh, Porter’s first memories as a performer were singing in church, “and then singing in school, and the teachers there hearing me sing and putting me in junior choir. But I grew up in a very religious household, so the only music in my house was gospel music. Until I could buy own music, that was all there was. Then in 6th grade I was introduced to theater — and that was the first time I got on stage — to do a musical.”

More Content from Metrosource[wpp range=”last10days” cat=’16259,26,19687′ thumbnail_width=75 thumbnail_height=50 limit=3 stats_views=0]

A House Is Not a Home

Otherwise, Porter says, “my childhood was the typical ‘you’re going to Hell’ story. It’s the same one that we’ve all heard over and over again, so to regurgitate that again is really to give it way too much energy,” he says. “I was 15 or 16, and I was trying hard to not be gay. But there was nothing I could hide, which was a problem, a little bit. But that was that, so I just … left. My only goal was to get out.”

It’s impossible to separate Porter’s less-than-welcome introduction to the world and his gritty determination to respond to bigotry with ferocious creativity. “I don’t know about all of that,” he says with a laugh. “At the time, my only goal was to get out of my situation. My circumstance in my youth was bullshit — so full of trauma — I just knew I had to get out. That was all that I was interested in doing. It was my entire focus. So whatever got me out was what I was gonna do; based on my talent, based on my skill. Whoever came into my life and treated me kindly and I felt like had my best interests at heart, I listened to them. I’ve had many angels in my life who reached out in that way, from middle school right up to today.”

Like many performers, Porter gravitated toward theater because it represented both an escape and shelter from his home life. The way he sees it, “I just like people. And it was the collaborative theater geeks that were there for me, and present in the most difficult parts of my life and sort of saved my life. So for me, it’s a chosen familial energy that I relied on for a very long time. And I still do.”

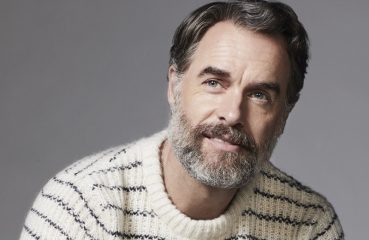

Billy Porter dressed for the Oscars — Photo courtesy ABC/Rick Rowell

What Friends Are For

Apart from those chosen few, compassion was hard to come by elsewhere. And Billy understood he was different before he knew what that difference was. “We’re talking about before any of us knew what being gay really meant. I mean, I didn’t really understand that at 11. But theater was a place that on the surface, if nothing else, was embracing. Theater embraced me in a way that people in my ‘normal’ everyday life outside actually rejected.”

Porter left home as soon as he could. At the outset, he says, “I wasn’t going to college. Honestly, it was the teachers I had: my drama teacher and my mentors in high school who more or less pulled me by my hair when they caught wind I was moving to New York City at 17. And they said, ’No, you’re going to go to college and learn a craft and actually understand what you’re doing so you can work for the rest of your life.’ It turned out to be the best thing anyone ever did for me because it’s all about access and it’s all about understanding that.”

For starters, Porter was informed that Carnegie Mellon was “a 10-minute drive from my house, and it was one of the top universities in the country.”

“We don’t get that kind of access,” he explains. “I discovered that I had the kind of talent that cracked open a different kind of access for me. And I understood that immediately.” So much of success, he suggests, “depends on who you are. It depends on where you come from. As a black gay man from poverty and the ghetto, I needed education. I needed a degree. I needed to learn what I was doing.”

Read Next | This Is Living Your Best Life: Caviar at Marky’s on Madison

Pass/Fail

Looking back, Porter muses that the source of his oppression ultimately proved his salvation. “Had I been able to pass for straight or whatever, I don’t know that anybody would have been challenged around me,” he says. “I don’t know that I would have been challenged to reach for anything different — because I would have been able to pass. And passing for straight was always considered better. And I couldn’t really do that naturally in a way that made other people comfortable, so I just had to lean into whatever it was that I had. Carnegie Mellon was very difficult because of that. My career was very difficult because of that. Theater people, the industry; as creatives we masquerade as being inclusive when it’s convenient, but we can be as homophobic as everybody else.”

While in college, Porter’s appetites reached out in every direction, including his taste in music. “Oh my, yes!” he recalls. “When I got to a place where I could buy my own stuff, and do my own investigating and researching — well, we didn’t have the internet then. That’s when I dove into Michael Jackson and all of that stuff. And that’s when I really fell in love with theater. I would check out records from the Carnegie library and that was how I got my music for a while. Then I started buying it and that’s how I caught up with the rest.”

To gain experience and add to his repertoire, Porter spent summers at Kennywood Park in a song-and-dance troupe called Flash. Their schedule was grueling. “There were a couple of groups,” he remembers. “Razzmatazz did Dixieland. They did a country show. It was six shows a day with a full band and three singers and every show was different. We did any kind of music you could think of, and I couldn’t even tell you what all. We sang every song you could ever imagine. Now I know the hooks to every song ever written because I did a music park show for three seasons. Flash was the singing and dancing ensemble, and we did our shows to tracks, and then the two casts came together at the end of the day for two nighttime shows.”

Read Next | This Is How the Beautyblender Can Refresh Your Look

Game Time

A B.F.A. in drama led to a certification from the screenwriting program at UCLA. And when people ask if so much higher education is really necessary when the work is largely creative, his reply cuts the question to its core. “Look,” he says, “I didn’t have the same kind of opportunities as my white counterparts who were famous 20 years before I got this opportunity — because they’re white. So I needed to back my shit up with real stuff. I’m just being honest. When I walk into the room with an undergraduate degree from Carnegie Mellon, a graduate degree from UCLA and two honorary bachelor’s degrees, white people listen to me. Period. You’ve gotta know what the game is.”

By 1997, Porter had already recorded his first album and appeared in two films, The First Wives Club and Twisted, in which he played a drag queen named Siniqua. The way he remembers it, “I was just showing up and walking through the doors that were open to me. It was the first time that anyone really gave me a job in film or TV. And it just happened to be a drag queen. I wasn’t really searching for it and I didn’t really feel like that’s who I was. I could do it, but I wasn’t pursuing female impersonating.

“I think there’s this idea that if you’re gay you’re obviously a drag queen. There’s a mentality about that. I went through a lot of it when I started doing Kinky Boots I had to put the kibosh on that whole “How long have you been a drag queen?” kind of question. My response became, “Did you ask that of Robin Williams when he made Mrs. Doubtfire? Did you ask Dustin Hoffman that after Tootsie? Stop it. What are you talking about? Why would you just assume because I’m black and because I’m gay that I’m a drag queen? No shade about being a drag queen, because I loved doing it. But I’m an actor who played a part and the part just happened to require me being a drag queen.”

Eclipse

Just as quickly as it began, his career slipped into retrograde. “I went out to Los Angeles and I made Broken Hearts Club in 1999 and it came out in 2000. And there was this thought in my brain that I could go out to Hollywood and ride on this gay thing. But it wasn’t quite the time, so I was there for almost three years and didn’t really have many auditions and didn’t get much interest. I was searching for my place in the business; my own lane. There weren’t a whole lot of things for me to be doing, based on the color of my skin alone. So when I heard Kinky Boots was going to be a musical and having seen the movie, I thought, ‘Well, that’s a part I could play.’ Had I been in London, I could have played that role in the movie. But when they announced it would be a musical, I sort of knew in my spirit that it was my shot. I never had a doubt in my mind. There were people around who thought I couldn’t do it, or had their doubts because I had taken myself out of the business for a while and hadn’t been on Broadway in 13 years. There were lots of questions.”

Billy Porter on the set of “Pose” — Courtesy JoJo Whilden – FX

Porter wouldn’t be denied a second time. “So I jumped through my hoops of fire just so that I could shut all that bullshit down. That’s why I stayed for three years, and why I stayed longer than anybody else — because I wanted everybody in the business to be clear: I know what I’m doing, and I’ve been doing it for 30 years. Please don’t question my skills anymore.”

His Kinky Boots Tony gave him the legitimacy he’d sought for so long, although he’ll admit: “it’s less about the award for me and more about being able to continue doing the work.”

Read Next | Li-Lac Chocolates Keep New Yorkers Coming Back for Tradition and Flavor

Murphy’s Law

Over the years, he’d also run into Ryan Murphy “in the sort of Gay Mafia circle that was just forming and coming up. We weren’t really friends; we just kind of knew of each other. And then he started doing all his stuff and heard me singing all these things, and I thought he was a person who would sort of understand me because his brand became taking all of this rarefied talent and exposing it. And really running toward it; not being afraid of theater people and the ‘bigness’ of us — which is something when you’re doing film and television that was always sort of a negative for me because of the choices I made.

“I knew he would understand me, so I just sort of started speaking him into existence. Ryan Murphy. Ryan Murphy. The law of attraction. I started writing him in my diary and saying for three years that Ryan Murphy will get it. And I got him, too. I saw Glee, American Horror Story, O.J. Simpson and I said, ‘Yeah, this is the guy.’”

When Murphy began casting Pose, Porter went in for an audition and knew immediately it was not the part for him.

“Pose came before American Horror Story. I got called in for an audition just the regular sort of way through my manager. “But by this time I had a Tony Award and a Grammy Award and a good reputation, and speaking up for myself would not be perceived as overstepping my bounds anymore. So I went in and read the part I was called in for, and then I said, ‘Okay, listen: I lived through this era. I think it would serve everybody if I was in that world because I’m from that world.’”

Porter pitched the possibility of playing a mother in one of the houses, then heard that Murphy wanted transgender actors in the roles. “I said, ‘That’s an amazing idea, but they’re going to need a father figure,” Porter recalls. “They’re going to need a male energy over there, right? Like a godfather, and there wasn’t one. There wasn’t a male leading man in the show. There was a lead boy, but not a grown man. So he called me in for a meeting and I just sat and talked to him. And so we talked about the emcee, and he had five lines in the first episode and it was not a character. And so he said, ‘Come in and I’ll create something for you.’ So that’s how it came about.”

Photo credit: Ron Cadiz © Sony Music Entertainment

Strike a Pose

Now that the show is about to debut its second season June 9, Porter has only one comment. “The only thing I’m authorized to say — because Ryan has said it — is that Season 2 opens the day Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ was released.”

From a broader view, he’s happy to be doing work that’s not only popular and recognized, but fills in some important blank spaces in cultural history. “I’m grateful that we’re finally telling the story of people of color,” he says. “We have made a lot of strides in LGBTQ storytelling and for the first 25 years, the mainstream version of it has mainly been about white people. I’m excited that people of color are at the front of our narrative and it’s being told by the people who were in it who were from that space.”

Knowing that his work, like his fashion choices, are staking a claim for queer dignity make him Proud. As he told Vogue after his Oscars TuxGown went viral, “my goal is to be a walking piece of political art every time I show up. To challenge expectations. What is masculinity? What does that mean? Women show up every day in pants, but the minute a man wears a dress, the seas part.”

It’s all part of Porter’s manifesto — that living well is not only the best revenge — it’s better than revenge. “My ministry is something different,” he says. “It’s authenticity in the face of abject oppression and phobia. Now, I think there’s a process of constant healing of fissures in my immediate family. But elsewhere I still hear the same kinds of abomination rhetoric I was hearing four years ago.

“You can go online and see all the comments,” says Porter, “and some of them are my people. There are people who would prefer me dead than to be successful. They’re talking shit on me still. Today. There’s always been this idea from the religious part of my life that these people are concerned for my soul, and that’s what motivates them to be hateful. That’s not what Jesus did; that’s not what the Bible says to do. F**k you. Get out of my life. I’m done. Don’t masquerade as Christians and blame your hate on Jesus. Stop doing that. What would Jesus do…? None of what you motherf**kers are doing. It’s in the Bible, what he did. I had to release that, because if you hold onto that energy, it will destroy you.”

Read Next | Lumos Dermatology: Get the Best Care for the Skin You’re In

Want Metrosource LGBTQ content notifications? Sign up for MetroEspresso.

Last modified: July 23, 2019